IGRUBI PROJECT

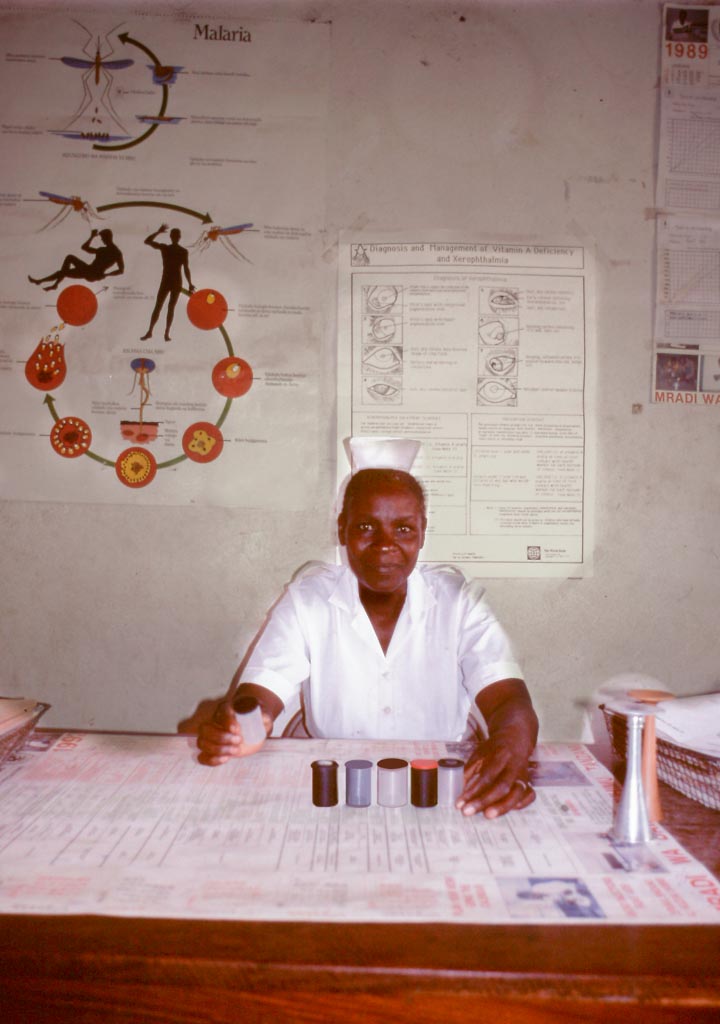

In 1992, shortly after leaving college, I was one of 20 volunteers helping to renovate a Health Centre whilst working for a charity called Health Projects Abroad. For eight weeks, we worked and lived within the small community of Igrubi town, a remote village in the Tabora region of Tanzania. Most afternoons, after we had finished our days work, I would stroll around Igrubi taking my camera with me.

These are some extracts from my journal:

The midwife has a startling white uniform with poppy red canvas shoes. I take a swig of warm water from my canister and some comfort because, the health centre is beginning to look cleaner. I smile at the splashed paint mistakes from today’s clumsy painting and notice many of the paintbrushes stained a royal blue sit in what remains of the white emulsion paint whilst the white stained brushes sit in another can of royal blue paint. I step outside and see a vision in orange. I recognise Heliwelu John. She pats her tummy, points and looks at me. We laugh and I blush. I am this stranger who has no children. She is a picture of complete composure. I leave her and see Anna’s house to the right, where green plants stand in the backyard. Anna is inside.

We drink chai (sweet tea) from plastic teacups. I notice a tree that stands out because it is covered with vibrant orange flowers. "It is the Christmas tree!" she announces. I find myself explaining what tinsel is. Passing a detached house, the smell of freshly cooked bread wafts around and you know that Grace, the head schoolteacher's wife is at home. A barren area appears ahead and this square of sand has to be crossed. I flip-flop along in my newly acquired sandals and feel cumbersome compared to the elegant ladies of a Igrubi. I have noticed that even the goats walk gracefully here. The local guesthouse appears ahead of me. Here in the back garden, the magician, Professor Singira, has swallowed many razor blades, which he then regurgitates and displays on the end of his pink tongue. He shows them off to all the paying villages.

Continuing my walk the scene ahead resembles a wild-west film set. The small dwellings are like cardboard cutouts and I want to rush behind them and push them down. I take a photograph of the butchers shop. I feel the presence of several pairs of eyes nearby. They are bewildered by my actions. After some silence, there follows uncontrolled deep laughter. Next door to the butchers there is a wooden stall on which I see tomatoes stacked in threes. Nearby, thousands of beady eyes stare at me from ‘dagar’ (dried fish) shimmering in the light.

I feel thirsty and cross the square to the local bar that serves warm beer and Coke from the fridge. There is no electricity. The local magistrate owns the bar. She is a hulk of a woman. She sits in her wheelchair observing the world and listening to the high-pitched shrill of Connie Francis. I’ve lost one of her empty beer bottles, which she wants returned. I sip my Coke and gulp. My smile hides my fear. I know the bottle has already been broken and sits in many pieces. I am doomed. I make a rapid exit and head further along the dusty path. I want to blend in but, because I have red hair and carry a Tesco’s plastic carrier bag, this isn’t possible. My presence is confirmed by shouts of “Sala, Sala”. Someone wants my attention.

I enter a shop and I’m initially startled to see my reflection in the full-length mirror. I cringe when I see myself. But then, from the corner of my eye, a notice pinned above me and written in bold print catches my attention. “A man’s success is measured not by how much money he has but by what kind of family he has brought up". Under the glass counter a shocking pink jar stands out between the tins of Vaseline. There too are displayed one size, brightly coloured, nylon knickers. Outside, George is busy pedalling away at his sewing machine. Kadenge, wearing his Michael Jackson T-shirt, greets me. I stop and sing a few bars of “Ben”. The glazed expression on Kadenge's face develops into huge bewildered smile.

In the cooler air, I head for the landscape where herdsmen wander with their cattle. The tinker of cowbells soothes my ear. I see before me a vast yellow fence, the bluest skies and one solitary cloud floating effortlessly by. An elder stands on the dust track proud and tall. His crisp white shirt is buttoned and an oval brimmed hat perches high on his head.

Hearing the murmur of life bubbling in the distance, I reluctantly walk back to wards my quarters. On the way I pass a rowdy “Pombe” house (Pombe is the local intoxicating brew). I am man handled by harmless, honey breathing beings. I feel like a jar of beetroot being passed around.

I take a shortcut through the maze of back alleyways to visit Bright Shabani, the local vet. He owns a tape of Lionel Ritchie’s greatest hits and two pink crochet seat covers. I disturb him. He is bathing the children and appears to be slightly flustered by my arrival but he smiles and announces, “You and Emma are famous”. I look puzzled. “You walk around the village”. I grin with amusement. “Will you be at the football on Sunday?” he asks. Thirsty again, I call in at the local hotel for ‘Chai’. The interior seems to be lighter than before. Is it due to the presence of a now familiar shade of royal blue paint? Pausing for a short while I grin and drink the last mouthful.

“Damn!, These batteries are bloody useless” I find myself struggling with my torch as I arrive back. I remember the words of a colleague. “Use your eyes, they will ajust”. I can see the outline of the Christmas tree and feel the presence of others quietly gliding alongside me.

“I’m Back” I shout to the others who are slumped on sleeping mats. The thought of cooking for eleven depresses me. “What’s that?” someone asks. I am clutching a little pink jar. “Beauty cream” I explain. “They had no Nivea!”